Syed Hammad Ali

For generations, the Indian family household has been governed by strict gender roles, where the men bear the responsibility of being the financial providers and protectors, while the women manage the household realms of child-rearing, cooking, and household maintenance. This division became so ingrained in our cultural identity that male self-worth has become intrinsically tied to economic output and stoic resilience. Boys learned early in life that showing vulnerability was a show of weakness; where phrases like ‘boys don’t cry’ and ‘man up’ reinforced emotional suppression as a core masculine virtue.

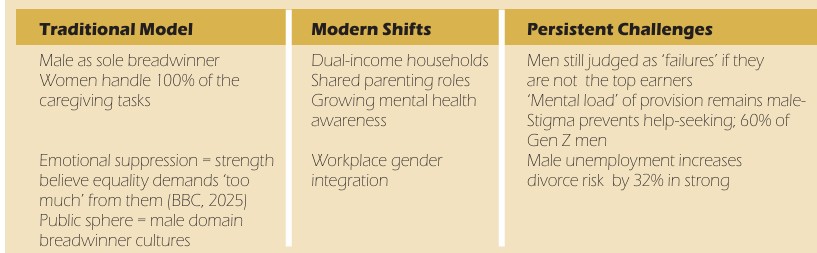

Despite modern sensibilities challenging this outlook, with increased dual-earner households emerging with shared domestic duties, the psychological legacy persists, particularly in Indian society. The expectation that men must remain the primary providers creates relentless pressure, where financial underperformance sparks shame, marital conflict, and profound identity crises (Marks et. al., 2009).

| Traditional Model | Modern Shifts | Persistent Challenges |

| Male as sole breadwinner | Dual-income households | Men still judged as ‘failures’ if they are not the top earners |

| Women handle 100% of the caregiving tasks | Shared parenting roles | ‘Mental load’ of provision remains male-dominated |

| Emotional suppression = strength | Growing mental health awareness | Stigma prevents help-seeking; 60% of Gen Z men believe equality demands ‘too much’ from them (BBC, 2025) |

| Public sphere = male domain | Workplace gender integration | Male unemployment increases divorce risk by 32% in strong breadwinner cultures |

Mental load of provision

The male ‘mental load’ extends far beyond income generation. It includes relentless cognitive labour that operates invisibly, yet is present throughout daily life. At its core lies risk management – the constant calculation of financial safety nets, emergency funds, and future security, which demands ongoing mental energy even during non-working hours. Compounding this is identity vigilance, where men unconsciously monitor their behaviours to avoid appearing ‘feminine’ or weak when discussing stress, forcing emotional suppression that contradicts internal struggles (Chatmon, 2020). Further intensifying the burden is social defence: the exhausting work of shielding families from societal judgment when earnings fall short of cultural benchmarks (Gonalons-Pons & Gangl, 2021). This triad of pressures triggers chronic stress, with studies revealing 72 per cent of unemployed stay-at-home fathers report intense shame, often labelled derogatory terms like ‘failed providers’ (BBC, 2025). The sustained stress levels increase the risk for cardiovascular disease, insomnia, substance abuse, and depression.

Stigma’s vicious cycle: Why men suffer in silence?

Cultural stigma transforms psychological distress into corrosive silence through three interconnected mechanisms. First, self-stigma leads men to internalise societal norms, viewing help-seeking as emasculating; research confirms men with depression avoid therapy fearing being judged as ‘broken’ (Shepherd et. al., 2023). Second, professional neglect occurs as mental health systems under-prioritise male-specific symptoms like anger, irritability, or escapist workaholism – resulting in critical underdiagnosis where fewer than 50 per cent of depressed men receive treatment despite 1 in 5 being affected. Third, social penalties manifest when ‘breadwinner failure’ triggers relational consequences: men outearned by partners face 11 per cent higher mental health diagnoses and elevated infidelity rates, often in the form of maladaptive attempts to ‘reassert masculinity’. These forces create a self-perpetuating cycle where distress remains hidden until crisis erupts. (McKenzie et. al., 2022)

Rewriting the script: Pathways to healing

Individual transformation begins with emotional re-education.

- One of the first steps towards this goal is practicing replacement of the reflexive ‘I’m fine’ with precise feeling words (‘overwhelmed’, ‘afraid’) to rewire neural pathways associating vulnerability with danger.

- Complementing this is task ownership redistribution using models like Eve Rodsky’s ‘Fair Play’, where men fully manage discrete household domains (e.g., finances or childcare scheduling) to equitably share cognitive labour.

- Crucially, developing physiological awareness through body scanning helps intercept distress early, as 90 per cent of men first experience it as physical tension (jaw clenching, stomach knots) before emotional recognition (Gonalons-Pons & Gangl, 2021).

Relational shifts require:

- Partners to initiate vulnerability through targeted questions like “What’s one work stress you carried today?” rather than generic inquiries.

- Values alignment exercises, such as selecting three non-negotiable priorities (e.g., ‘children’s education’) and discard outdated tasks unrelated to core needs.

- Regularly voicing credit affirmations (“I see how you protected our peace by handling those repairs”) validates non-financial contributions that traditionally go unseen.

Systemic advocacy must push workplaces to mandate meeting-free hours for therapy and ‘provider pressure’ workshops teaching burnout identification (fatigue, cynicism, reduced efficacy). Schools can counter toxic messaging by integrating emotional literacy modules where boys learn to articulate sadness and fear – directly challenging the ‘boys don’t cry’ dogma. Policy reforms should emulate Sweden’s ‘daddy months’, reserving paternity leave to normalise male caregiving and dismantle provider exclusivity.

Toward a culture of collective resilience

The collapse of the ‘strong provider’ archetype under modern economic sensibilities demands redefining strength through shared provision, expressive vulnerability, and professional support. The goal isn’t eliminating men’s provider roles, but transforming provision from a solitary burden into a collective act of care.

References

Chatmon B.N. (2020). Males and Mental Health Stigma. American journal of men’s health.

Gonalons-Pons, P., & Gangl, M. (2021). Marriage and Masculinity: Male-Breadwinner Culture, Unemployment, and Separation Risk in 29 Countries. American sociological review.

Hogenboom, M. (2025, May). Why money and power affect male self-esteem. BBC.

Marks, J., Bun, L.C., & McHale, S.M. (2009). Family Patterns of Gender Role Attitudes. Sex roles.

McKenzie, S.K., Oliffe, J.L., Black, A., & Collings, S. (2022). Men’s Experiences of Mental Illness Stigma Across the Lifespan: A Scoping Review. American journal of men’s health.

McKenzie, S.K., Collings, S., Jenkin, G., & River, J. (2018). Masculinity, Social Connectedness, and Mental Health: Men’s Diverse Patterns of Practice. American journal of men’s health.

Shepherd, G., Astbury, E., Cooper, A., Dobrzynska, W., Goddard, E., Murphy, H., & Whitley, A. (2023). The challenges preventing men from seeking counselling or psychotherapy. Mental Health & Prevention.

Syed Hammad Ali works as a Counselling Psychologist and Academic Coordinator at Vimhans Hospital, Delhi. An University of Glasgow MSc graduate in Psychological Studies, his experience spans direct care for adults with mental health needs, certified Clinical Hypnotherapy practice, and assisting psychological research. His passion for psychology extends to exploring its connections with poetry and theatre. Off-duty, he recharges with board games, video games, and getting lost in compelling fanfiction, valuing these creative and strategic escapes.