Written By Sharad Kohli

Our lives are colliding with the uncontainable forces of climate change, both emotionally – in the flower that blooms late, in the clingy heat that outstays its welcome when Maa Durga comes calling – and certainly physically, at least among those of us who have experienced the fear of floodwaters entering our homes, or the dread of extreme heat leaving us disoriented and delirious. As we grieve for what’s been lost, how do we find a way back? This is an ode to seasons past in an endeavour to look for the answers.

Out on farms in rural India, where tillers of the soil spend days under a hostile sun, the heat and humidity can be killing – literally. Months without a drop of rain are as soul-sapping as torrents that refuse to cease, and lightning strikes are becoming deadlier. In city slums, meanwhile, corrugated-iron roofs make life stiflingly uncomfortable for families whose only home, come rain or shine, is a shack unfit for a warming climate.

It is important for us urban folks to leave our biases at the doorstep, to include in our conversations – and also be conscious of – the experiences of people who live off the land or the sea, and who have it far, far worse. Because, climate change is this era’s great equaliser, a challenge we all must face together, even if our ways of coping differ.

On a February day when a national daily carried a report suggesting that spring might soon disappear, I nursed my disenchantment by listening to Raag Basant. It was spring alright, the vernal sun pouring out its goodness from a blue sky while a stiff wind let us know that winter had yet to loosen its grip. But for how long will spring linger this year.

Ah yes, spring, a season so treasured, one that brings with it the promise of renewal and relief after the many foggy dawns and dusks, and bone-chilling sunless days, of the north Indian winter. The report mentioned how practices that have been part of local cultures for as long as the land and the people have been joined at the hip, are being disrupted by a climate that grows steadily more unstable by the year. Indeed, we may have to accept that the rhythms of seasons, measured yet obvious, and the little cues that marked each phase of transition, aren’t as palpable as they once used to be.

Still, if we are to resist the monster that climate change has become, it is vital that we return to the community around which our days and nights once revolved, to remind ourselves how interwoven the seasons were in the warp and weft of our past lives.

‘The ocean is the river’s goal

A need to leave the water knows’

(Find the River, R.E.M.)

Wintering to my heart’s content

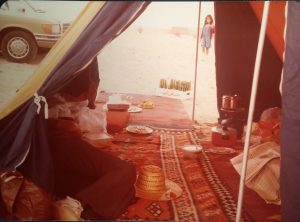

While I did spend Decembers and Januarys in England – months of frost and mist, and of days without end without sun – it is the winters of Arabia whose memories remain as fresh as a morning after a night’s rain: Kuwait, with her bracing and breezy cold, and her reverberating thunderstorms that would roll off the desert, and (for a very short while) Dubai, not as chilly and atmospherically less dramatic. The rains, when they did arrive in this part of the world (usually in winter or spring), were stubborn in their intensity and life-affirming in their bounty. However, of late, both Kuwait and Dubai endured unprecedented downpours, which threw everyday life out of kilter. This ‘new normal’ would have felt alarmingly abnormal back in the 1980s, when to be out of doors in the cold weather was to feel invigorated.

The brief rapture of spring

I was lucky enough to spend a week each in Dublin and Galway, in beautiful Ireland, just as spring was unfurling her charm. I was even luckier that my stay in Dublin (and, for a few days, in County Wicklow, to the south of the capital) coincided with a burst of early summer. It was warm enough certainly to roam the streets sleeveless, and the city turned lovelier under a benevolent May sun. A year later, in Galway, it rained every day, but when the sun emerged from the slate-grey clouds, it did so with a resplendence that took your breath away. It was, in fact, that type of spring, when showers magically gave way to sunshine, when there was always the chance of a rainbow on the horizon. The weather may have been gloomy, but, gosh, the trip was far from it.

Yet, it is the spring of Delhi that will stay long in the memory, a spring all the more gorgeous because, well, she would soon be gone, like a lover breezing in and then out of one’s life. The Mughals, as sensitive to (and emotionally invested in) nature’s beauty as any of India’s rulers, left behind poetry and prose rhapsodising feisty Dilli’s fleeting spring, when the city was at her finest. The season’s evanescence was all the more wistful because of what followed: the intolerable summer, the loo and dust squalls, and the feeling of trepidation these evoked.

Desperately seeking shade

If there was any occasion in the past when I might have foreseen a world buffeted by climate extremes, it was during the school holidays in Kuwait. Summers in the small, oil-rich emirate crept up on you and before you knew it, there was no escaping the furnace. In Kuwait, as in much of the Arabian Peninsula, highs of 50°C and above are not uncommon, with temperatures hovering in the mid to late 40s across June, July and August. These summers sizzled, sweltered and blazed, and the evenings – even the nights – brought little respite from the insufferable heat.

Yet, 50°C days may no longer be freak events, not when fossil fuels continue to be burnt recklessly. In 2024, wave upon wave of heat pummelled the Subcontinent, disproportionately affecting the many on the margins, those whose lack of agency leaves them with no option but to work under the unforgiving – and increasingly lethal – glare of the midday sun. A childhood memory had become an adult reality, a disquieting sign of the times.

If summer in Kuwait was a punishment, the one in England was bliss and balm. As a boarder in Shrewsbury, Shropshire, a brown face in a sea of white faces, it was the weather that kept me from drowning in homesickness. And I refer not only to those gloriously cerulean-sky sunny days that seemed to last forever, but also days made for games and barbecues and concerts in the park. Just as memorable were the days when the sun made a cameo appearance, peeking through a bank of clouds to provide welcome warmth and remind this boy of home. And it seemed to shine all the more brilliantly in the late afternoon or early evening, after a particularly gloomy and damp spell.

If the thermometer touched 25°C, the shirts came off; if it crossed that mark, they declared a heatwave. Now, temperatures beyond 30°C are not uncommon. As a geography textbook of my schooldays predicted, Britain’s summers would come to resemble those of the Mediterranean; if it weren’t blustery and wet, it would be hot and dry, perfect conditions for mad dogs and Englishmen to thrive (before storms spectacularly turned up to rain on their parade).

‘Thandi hawa, kali ghata’

The rain I knew from Kuwait and England did not prepare me for the fury of the Indian monsoon. No, those were mere puddles in front of this turbulent ocean. Black thunderheads heralded the arrival of a meteorological phenomenon whose importance to India’s agriculture and culture is undeniable, and to which paeans and ballads have been written. The sheets of rain that tumble down from the skies, accompanied by pyrotechnic displays of thunder and lightning, awaken the earth from its torpor and colour it with a green most lush.

But as much as it rejuvenates, the monsoon can also leave the land defenceless in the face of its wrath, its power to revive as strong as its propensity to wreak havoc. Floods and landslides have become more frequent because of dams, unchecked development, and the stupidity of building over centuries-old water bodies. As for experiencing the romance of the rains, you’ll have to travel as far away from concrete living spaces as it’s possible to; to places still not colonised by the destructive habits of man. Or, you can listen to Raag Miyan Malhar, and let its beauty wash over you.

‘Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun’

And so we come to autumn, the season of soft light, muted hues, harvested thoughts and reflection. I have spent autumns in pastoral Shropshire, in a land where Keats composed an ode to the season, one of the most beautiful poems in the English language. And truly, an English autumn, personified by the mellow gold of the countryside and restorative warmth of the sun, can bring out the versifier in you. At this time of year, the land doesn’t call attention to itself; it just is, fulfilled in labour and restful in spirit. A part of this Shropshire Lad yearns to return, to see for himself if the autumn of his youth remains.

On the other side of the world, in Japan, autumn’s rhythms are graceful, even amid the atmospheric tumult of typhoon season. Two visits, seven years apart, offered a tantalising glimpse into this East Asian nation’s timeless traditions, and its people’s imperturbability and their unshakeable faith in nature. A couple of days in Kawagoe City presented two sides of autumn, one rainy and windy, courtesy a storm blowing in off the Pacific, the other magnificently sunlit, the season’s deep greens and russets putting on a grand show. Later, I saw Tokyo at its autumnal best, the city’s gardens and parks whispering in a language only the heart and soul could understand, as blue sky gave way to drizzly interludes, the breeze adding a ‘spring’ to one’s step.

Let the healing begin

We can’t bring our childhood back, as much as we all yearn to. We can’t wish the seasons of our youth back; we’re too far gone in a post-climate-change world for that to happen. And we can’t undo the despoliation that has been visited upon Planet Earth, an eco-terrorism fuelled by greed, tyranny and narcissism. The best we can do amid the apprehension and the anxiety is to embrace community, to trust in and support each other. And to seek to create an emotional and spiritual equilibrium, one that is centred in nature: delicate, vulnerable nature. We can again, just like we once did, before we stopped reading between the lines and mislaid whatever little empathy we had.

In these often fearfully uncertain times, our spirits can guide us, and our hearts light the way. Still, to imagine a better and more sustainable world, we need to adopt a new consciousness around nature, one in which every ecosystem is our ally, each season a fellow traveller in our journeys around the sun. We need to feel again what it means, collectively, to move in step with the pulse of the earth, to dance again to the music of the land.